Last week the Reserve Bank came out with the latest of its Analytical Notes - a series I highly recommend. They're pitched at the intelligent citizen, and they also have a 'non-technical summary' at the front, so even if monetary policy or macroeconomics isn't your go-to choice for a light read, you'll find the material both accessible and interesting.

This latest one is more interesting than most - "Estimating New Zealand’s neutral interest rate", by Adam Richardson and Rebecca Williams. Obviously the Bank needs a view on the neutral rate so as to know whether its setting of the cash rate is on the side of policy stimulus or on the side of policy constraint, but it's also interesting for the rest of us, as it's a pointer to whether borrowing costs are relatively low or relatively high.

Intuitively I think we all know what a 'neutral rate' is, but it's harder to pin down an exact definition. The paper says that the neutral rate is "a level of the nominal 90-day bank bill rate that it [the Bank] believes is neither expansionary nor contractionary" and "the interest rate that would prevail once all business cycle shocks have dissipated and inflation is expected to remain at target". The paper doesn't mention where the exchange rate would be at the time, but I suppose we have to assume that the exchange rate is at some middle-of-the-road, purchasing-power-parity sort of level.

The interest rate that would prevail in 'normal', neither boom nor bust conditions, and that would be consistent with inflation steady and the Bank being able to stand pat, is, as the paper says, not directly observable, as things are never going to stand still long enough for you to measure it. So you've got to sneak up on it, and the authors did so from five separate directions. Unsurprisingly the different perspectives give different answers for the neutral 90 day bank bill rate: the range of answers is shown in the graph below. The average is 4.3%, and the Bank's current operating assumption for its policymaking is there or thereabouts, at 4.5%. The Bank's take on the neutral floating mortgage rate, by the way, is 7%, or the neutral 90 day bill rate plus a 2.5% margin.

It's interesting that four of the five approaches have the neutral rate falling. One approach has it bottoming out around the end of the GFC, in 2009-11, but rising quite strongly since, which seems on the implausible side. The ones that have the neutral rate falling, generally have it falling most during and post the GFC period, which seems reasonable: the world seems to be a different place since in a number of respects (including, for example, wage-setting).

But it may not all be down to the GFC: one of the approaches has the neutral rate falling steadily since around the turn of the millennium, and that also makes some sense to me. You'd expect that the Bank would have garnered some increased policy 'credibility' (as the jargon has it) over that period. People would have come to believe more strongly - the odd misstep apart - that the Bank was on top of its inflation-targetting brief. And as they did, the Bank would have been able to exert more effective pressure with less effort, the proverbial 'bigger bang per buck', which is another way of saying that the neutral rate must have gone down.

If anything, I'd say the Bank's operating assumption of 4.5% is a bit on the high side. For one thing, it would be near the top of that target band in the graph, if you discounted the one approach that has the neutral rate rising (and which is responsible for the 4.8% top of the shaded band). And for another, if I put a fund manager's hat on, I'd say that there ought to be a low, and maybe close to zero, long-term after-tax real return to holding cash. At 2% inflation (middle of the target range) and a 28% corporate tax rate, bills at 4.5% would offer a tax paid nominal return of 3.24% and a real after tax return of 1.22%. Or for holding cash (say 20 basis points below bills) an after tax real return of 1.07%. In current circumstances, that looks a return that's on the high side for a liquid risk-free asset.

Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Saturday, 26 September 2015

Who's been 'buying up' New Zealand?

There's a huge interest in foreign investment in New Zealand - it's front page news when Chinese investors aren't allowed to buy farms, or Asian investors are supposedly snapping up Auckland houses, and the piece I wrote about Statistics NZ's data on foreign direct investment has had by far the biggest number of pageviews of anything I've written recently. Yeah, yeah, yeah, I know, they're not Krugmanesque numbers, but still.

Yesterday Stats released an update to the numbers, showing the situation at the end of March '15 (the spreadsheet with the numbers is here). First, here's the total stock of foreign direct investment in New Zealand, which includes the likes of those farms.

Yesterday Stats released an update to the numbers, showing the situation at the end of March '15 (the spreadsheet with the numbers is here). First, here's the total stock of foreign direct investment in New Zealand, which includes the likes of those farms.

One country overshadows everybody else. Australia has more invested here ($51.4 billion) than the rest of the world put together ($48.2 billion). There are bite-sized chunks from the US, Hong Kong, the UK and a range of other Asian and European countries, but the story starts and ends with Australia. Most of Australia's interest is the banks: I don't have a complete industry-by-country breakdown, but given that there's $32.1 billion of overseas investment in our 'financial and insurance services' sector, and that by far the bulk of that will be the Aussie-owned banks, you can say that about 60% of all Australian investment is in the finance industry.

And what about all those farms being sold out from under the feet of our own farmers? Nah. Total FDI in 'agriculture, forestry and fishing' is $5.9 billion, a small proportion (5.9%) of the total investment, and roughly on a par with foreign investment in the retail trade ($5.7 billion).

It's also a very small proportion of the total value of farms and forests, which at a heroic guess (as I'm no expert on the data in this neck of the woods) I put at around $340 billion. That's 14.4 million hectares (2012 Agricultural Census, here) times an average price these days of some US$15,000 a hectare (which I got from this article), or NZ$23,500 or so at today's exchange rate. So roughly only 1.7% of agriculture is owned overseas, and of that I'd guess a fair slab is foreign institutional fund ownership of forests. The proportion of the archetypal family-run sheep and beef or dairy farms owned by overseas interests must be very small indeed.

For those who might be agitated that we're all in hock to the People's Bank of China, that doesn't show up, either. Here's the picture of total foreign portfolio investment - everything from government stock to listed shares to unlisted equity to money lent to New Zealand entities. Essentially it's the UK, the US and Australia, with roughly equal amounts, and there's a modest bit from Japan. Everything else is relatively insignificant.

Thursday, 24 September 2015

What competition problems have we got?

The Commerce Commission released the second of its Consumer Issues Reports today, and it's full of interesting stuff: here's the press release and here's the full report (pdf), and there's also an infographic, if you're into infographics.

There's quite a lot of media coverage already of the Fair Trading Act parts of the report - which companies and which sectors have most riled customers - so I won't go over the same ground. Thinking about the current Volkswagen debacle, all I'll add to the Fair Trading Act coverage is that while the Act is often seen as predominantly protecting the retail final consumer, it also has an underappreciated role in protecting good businesses from shady behaviour from their competitors, and in preventing the sort of "everyone's doing it" race to the bottom that seems to be part of the Volkswagen story.

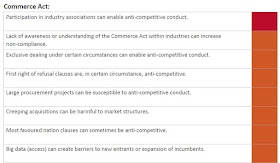

Instead, I'm going to focus on the Commerce Act competition issues. The report uses this matrix to grade them in terms of seriousness -

The good news is that there's only one item in the red 'very high' detriment box, but it's a biggie that's been known internationally for some time to be a problematic area: industry associations overstepping the mark.

Businesses can have perfectly good reasons to cooperate and coordinate, and consumers will often benefit: indeed, failure to cooperate (in areas like telco number portability, for example) can prove to be serious impediments to consumers getting a good deal. But there's a line beyond which cooperation shades into collusion. As the report says (p29), "Industry associations continue to feature in investigations into price fixing agreements and/or agreements that substantially lessen competition, particularly where an external shock or cost has affected members".

If I were actively involved in an industry association - and I use "industry" broadly to include health and education - I think I'd be taking an urgent interest in exactly how far the association has gone along the cooperation/collusion spectrum, as there's a very high likelihood that this red box will be guiding the Commission's future investigative direction (if it isn't already). Fortunately there's any number of lawyers and (ahem) economists who can assist.

There's something of a common thread to three of the 'high risk' brown box items - exclusive dealing, first right of refusal, and most favoured nation. It may be that the Commission is mostly thinking of the electricity lines businesses - "Many complaint narratives are concerned with possible anti-competitive behaviour exhibited by lines companies operating in regional monopolies, keeping closed relationships with subcontractors, charging customers excessive prices, and pressuring customers to pay for necessary infrastructure" (p28) - but we'll have to wait and see what else might be lurking in the bushes. If you are a company that makes much use of exclusivity-style clauses in your contracts, again I think I'd be getting some second opinions.

The last one, access to 'big data', takes us into the general territory of things like the EU's current go at Google. How much progress the Commission might make on these kinds of issues, however - assuming they are indeed live issues in New Zealand - is anyone's guess, but the best guess is slim to none.

For one thing, the intellectual economic and legal issues in these kinds of cases are everywhere both highly complex, and unsettled. For another, almost by definition you're into s36 territory (abuse of a position of substantial market power), and that sends you crashing into two New-Zealand-specific obstacles. The courts have, after extensive, careful and learned consideration, gutted s36, and the policy wallahs at MBIE who've been asked to look at the problem haven't yet emerged from their transcendental trance. If there are serious issues in this space, the Commission has a half of five eighths of [insert your favourite metaphor here] chance to do something about it.

There's quite a lot of media coverage already of the Fair Trading Act parts of the report - which companies and which sectors have most riled customers - so I won't go over the same ground. Thinking about the current Volkswagen debacle, all I'll add to the Fair Trading Act coverage is that while the Act is often seen as predominantly protecting the retail final consumer, it also has an underappreciated role in protecting good businesses from shady behaviour from their competitors, and in preventing the sort of "everyone's doing it" race to the bottom that seems to be part of the Volkswagen story.

Instead, I'm going to focus on the Commerce Act competition issues. The report uses this matrix to grade them in terms of seriousness -

- and I've clipped this list of the top ones ('very high' and 'high' level of detriment) from the full list of Commerce Act issues on p51.

The good news is that there's only one item in the red 'very high' detriment box, but it's a biggie that's been known internationally for some time to be a problematic area: industry associations overstepping the mark.

Businesses can have perfectly good reasons to cooperate and coordinate, and consumers will often benefit: indeed, failure to cooperate (in areas like telco number portability, for example) can prove to be serious impediments to consumers getting a good deal. But there's a line beyond which cooperation shades into collusion. As the report says (p29), "Industry associations continue to feature in investigations into price fixing agreements and/or agreements that substantially lessen competition, particularly where an external shock or cost has affected members".

If I were actively involved in an industry association - and I use "industry" broadly to include health and education - I think I'd be taking an urgent interest in exactly how far the association has gone along the cooperation/collusion spectrum, as there's a very high likelihood that this red box will be guiding the Commission's future investigative direction (if it isn't already). Fortunately there's any number of lawyers and (ahem) economists who can assist.

There's something of a common thread to three of the 'high risk' brown box items - exclusive dealing, first right of refusal, and most favoured nation. It may be that the Commission is mostly thinking of the electricity lines businesses - "Many complaint narratives are concerned with possible anti-competitive behaviour exhibited by lines companies operating in regional monopolies, keeping closed relationships with subcontractors, charging customers excessive prices, and pressuring customers to pay for necessary infrastructure" (p28) - but we'll have to wait and see what else might be lurking in the bushes. If you are a company that makes much use of exclusivity-style clauses in your contracts, again I think I'd be getting some second opinions.

The last one, access to 'big data', takes us into the general territory of things like the EU's current go at Google. How much progress the Commission might make on these kinds of issues, however - assuming they are indeed live issues in New Zealand - is anyone's guess, but the best guess is slim to none.

For one thing, the intellectual economic and legal issues in these kinds of cases are everywhere both highly complex, and unsettled. For another, almost by definition you're into s36 territory (abuse of a position of substantial market power), and that sends you crashing into two New-Zealand-specific obstacles. The courts have, after extensive, careful and learned consideration, gutted s36, and the policy wallahs at MBIE who've been asked to look at the problem haven't yet emerged from their transcendental trance. If there are serious issues in this space, the Commission has a half of five eighths of [insert your favourite metaphor here] chance to do something about it.

Tuesday, 22 September 2015

A peek behind the veil of ignorance

Last week's post about a paper that documented the remarkable level of economic ignorance amongst New Zealand's business managers seems to have hit the spot, going by page views and comments.

Comments have been somewhere on a spectrum between head-shaking bafflement and outright incredulity, with a soupçon of "how can people this ignorant stay in business?". And, mostly, I'm somewhere in that range myself.

But one commenter pointed me to something that shows managers' beliefs in a modestly less awful light. It's an earlier paper by largely the same people, 'How do firms form their expectations: new survey evidence', an NBER working paper from April of this year. The abstract is here, but the whole thing will cost you US$5 unless you 're in academia or the media or a developing economy: us common or garden bloggers have to pay up, and I did. Oh, and the NBER is funny about copyright, so here it is - © 2015 by Olivier Coibion, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Saten Kumar.

What this paper found is that managers may be terrible at estimating the current or likely rate of consumer inflation - no better than the populace at large, which seems rather strange for people at the business coalface - but they are rather better at knowing what producer prices are doing in their industry. Here's the graph that shows it.

The left-hand panel A shows the distribution of managers' estimates of various recent macroeconomic data - the inflation rate in their own industry, inflation overall, GDP growth, and the unemployment rate. Negative values mean that the managers' estimates are too high relative to the real number.

Managers aren't too bad at getting their own sector's inflation rate right: on average, in fact, they're bang on, though there's still quite a big dispersion around the right answer. They're reasonably good at the unemployment rate (they have it a little higher than it really is), but not so hot at GDP growth (they have it about 1.5% - 2.0% higher than reality, from eyeballing the graph). And as my previous post said, they're really bad at the CPI inflation rate, being well off the mark on average and with estimates all over the shop.

The authors show that you can explain the managers' ignorance of the true rate of inflation in terms of 'rational inattention' - life's too short to be on top of everything, and if it's not important to you, you don't bother. Equally they show that managers who think inflation is important for their business do a better job of tracking it, and as we've seen in the graph above, managers stay on top of their industry's inflation pretty well, given that they've got both the incentive and the opportunity. And the paper's authors also show that if you give managers some additional information on actual and forecast data, they improve their estimates. Managers, in sum, aren't the complete ignoramuses you might have imagined when (for example) you see their level of ignorance about the basics of what the Reserve Bank does.

But it all still leaves that basic question: why do so many managers think inflation isn't important to them, and hence or otherwise get it so wrong?

There'a clue in the right-hand Panel B. It takes the (badly overestimated) inflation estimates in the left-hand panel, and breaks them out by the sector of respondent. You can see that there's a decent proportion of people in manufacturing and trade who have an accurate idea of inflation (though even then there's a tail of people with shots that are too high). But there isn't even a semblance of getting within cooee of the right answer for the average managers in professional and financial services firms, or in construction and transport businesses.

So here's my interpretation, not the authors' (though there are also bits of the paper that point the same way, such as the bit that shows managers in businesses with more competition pay more attention to inflation). That sectoral breakdown in Panel B is pretty much along tradables/non-tradables lines. Managers in tradables sectors have to be reasonably okay at getting inflation right, as there are enough competitors (domestic and overseas) who will eat their lunch if they're systematically bad at it. And managers in non-tradables sectors don't have to be, because there aren't.

I've thought it before, and I'm thinking it again: there are a lot of businesses in non-tradables sectors who can coast on a cost-plus mentality, and I doubt if we're going to make much inroads on our national productivity issues until stronger competitive pressures are brought to bear on them.

Comments have been somewhere on a spectrum between head-shaking bafflement and outright incredulity, with a soupçon of "how can people this ignorant stay in business?". And, mostly, I'm somewhere in that range myself.

But one commenter pointed me to something that shows managers' beliefs in a modestly less awful light. It's an earlier paper by largely the same people, 'How do firms form their expectations: new survey evidence', an NBER working paper from April of this year. The abstract is here, but the whole thing will cost you US$5 unless you 're in academia or the media or a developing economy: us common or garden bloggers have to pay up, and I did. Oh, and the NBER is funny about copyright, so here it is - © 2015 by Olivier Coibion, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Saten Kumar.

What this paper found is that managers may be terrible at estimating the current or likely rate of consumer inflation - no better than the populace at large, which seems rather strange for people at the business coalface - but they are rather better at knowing what producer prices are doing in their industry. Here's the graph that shows it.

The left-hand panel A shows the distribution of managers' estimates of various recent macroeconomic data - the inflation rate in their own industry, inflation overall, GDP growth, and the unemployment rate. Negative values mean that the managers' estimates are too high relative to the real number.

Managers aren't too bad at getting their own sector's inflation rate right: on average, in fact, they're bang on, though there's still quite a big dispersion around the right answer. They're reasonably good at the unemployment rate (they have it a little higher than it really is), but not so hot at GDP growth (they have it about 1.5% - 2.0% higher than reality, from eyeballing the graph). And as my previous post said, they're really bad at the CPI inflation rate, being well off the mark on average and with estimates all over the shop.

The authors show that you can explain the managers' ignorance of the true rate of inflation in terms of 'rational inattention' - life's too short to be on top of everything, and if it's not important to you, you don't bother. Equally they show that managers who think inflation is important for their business do a better job of tracking it, and as we've seen in the graph above, managers stay on top of their industry's inflation pretty well, given that they've got both the incentive and the opportunity. And the paper's authors also show that if you give managers some additional information on actual and forecast data, they improve their estimates. Managers, in sum, aren't the complete ignoramuses you might have imagined when (for example) you see their level of ignorance about the basics of what the Reserve Bank does.

But it all still leaves that basic question: why do so many managers think inflation isn't important to them, and hence or otherwise get it so wrong?

There'a clue in the right-hand Panel B. It takes the (badly overestimated) inflation estimates in the left-hand panel, and breaks them out by the sector of respondent. You can see that there's a decent proportion of people in manufacturing and trade who have an accurate idea of inflation (though even then there's a tail of people with shots that are too high). But there isn't even a semblance of getting within cooee of the right answer for the average managers in professional and financial services firms, or in construction and transport businesses.

So here's my interpretation, not the authors' (though there are also bits of the paper that point the same way, such as the bit that shows managers in businesses with more competition pay more attention to inflation). That sectoral breakdown in Panel B is pretty much along tradables/non-tradables lines. Managers in tradables sectors have to be reasonably okay at getting inflation right, as there are enough competitors (domestic and overseas) who will eat their lunch if they're systematically bad at it. And managers in non-tradables sectors don't have to be, because there aren't.

I've thought it before, and I'm thinking it again: there are a lot of businesses in non-tradables sectors who can coast on a cost-plus mentality, and I doubt if we're going to make much inroads on our national productivity issues until stronger competitive pressures are brought to bear on them.

Friday, 18 September 2015

Extraordinary ignorance

We got a remarkable insight recently into something very odd indeed in New Zealand, and it came from a rather unlikely source, the latest Brookings Papers on Economic Activity conference.

One of the papers presented was 'Inflation targeting does not anchor inflation expectations: Evidence from firms in New Zealand', a paper with four co-authors, one being AUT's Saten Kumar. You can read the abstract and media release, or the whole paper: even if you don't often read more academic papers, this one's worth it. It's pretty easy to follow - indeed, the authors have a rather non-academic flair for making their points crisply and colourfully.

The main focus of the paper is whether inflation expectations are 'anchored': roughly, do people clearly believe that inflation will stay reliably low? They look at five possible ways of assessing it: for example, do expectations vary very widely across the population rather than most people being in the same sort of place? Do expectations jump all over the place from one time period to the next? And so on.

On all five criteria, they find that the business managers they polled did not have settled inflationary expectations. As the abstract puts it

But it also says something pretty damning about the level of ignorance among New Zealand's business community. I'll pass quickly over the facts that only 31% of managers could identify the main objective of the Reserve Bank, and that only 30% could name its governor (even when, in both cases, they were given prompt sheets of the possible answers), and concentrate on this one. Here's a table (clipped from table 7 of the paper) of responses to the question, what inflation rate do you think the RBNZ is trying to achieve? Column 1 shows the possible answers, column 2 shows the percentage of managers who opted for each possible answer, and column 3 shows what they thought actual inflation would be over the following year.

As the authors summarised it, "Of the respondents, only 12% correctly responded 2%, although an additional 25% said either 1% or 3%, the bottom and top of the target range of the RBNZ. But 15% said the RBNZ’s target inflation rate was 5%, 36% said the target was more than 5%, with 5% of respondents saying that the RBNZ’s target inflation rate was 10% or more". Just over half (50.9%) thought that inflation was going to be at least 5%. It turned out to be 0.8% (year to December '14).

Now, I know that there will be a lot of managers doing a perfectly acceptable job of getting the widgets made and out the door, with or without knowing what the rate of inflation is or exactly what the Reserve Bank is trying to do. I'd suggest, particularly if they come anywhere near the strategic planning end of the business, that they're nowhere near as effective as they might be, but there's surely a valid role for heads down, bums up, and get the salads packed and despatched.

And I know that those of us who are into macroeconomics can sometimes forget that others aren't as familiar with the jargon and the details, and that you can actually have a life without delving into the national accounts or the CPI. People get caught up in their own preoccupations, but we don't all need to know the niceties of the LBW rule.

And I know that other countries can be just as bad: the paper documents a similar pattern in the US, though that's little comfort. Not many of us would like to be found on a par with what's happening in twilight Trump-or-Cruz America.

Apologetics apart, though, let's face it: this is a staggering level of ignorance. It makes you ask, among many other things, what on earth the secondary schools can have been teaching in their economics classes over the last twenty years. It leaves you thinking that one of the reasons for our well-documented issues with productivity might well be ill-equipped management. And it makes you wonder about the level of understanding voters have brought into the polling booths: as I've written before, every general election has brought proposals for changing our monetary policy regime, ranging from the potentially promising to total nonsense. How likely is it we'll get a good outcome when people have only the foggiest idea of the current arrangements?

A statistical addendum The first, and often the only, rule when you find extraordinary data like these, is that the data are wrong. They've been mismeasured, someone didn't clean the test tubes, there's an error in the spreadsheet. And I can't quite shake the doubt in this case that there might be a self-selection bias in the survey the researchers carried out. When they first sent the questionnaires out, they got a 20% response - a pretty good outcome. But what if the more clued-in managers opened the envelope and said, "Jeez, I've done enough of these, I'll pass", and the less clued-in ones said, "Wow, no-one's asked for my opinion before"? And if that happened, the potential self-selection bias probably became more acute as an issue in later waves of the survey, since the researchers only went back to people who responded to the first wave. There's a risk that the surveys could have progressively zeroed in on the most clueless. Whether it happened, or what difference it might have made, I can't tell, and it might be completely off the mark, so I'll take the data at face value. Overseas evidence of the same ignorance is rather suggestive that this paper is broadly right anyway.

One of the papers presented was 'Inflation targeting does not anchor inflation expectations: Evidence from firms in New Zealand', a paper with four co-authors, one being AUT's Saten Kumar. You can read the abstract and media release, or the whole paper: even if you don't often read more academic papers, this one's worth it. It's pretty easy to follow - indeed, the authors have a rather non-academic flair for making their points crisply and colourfully.

The main focus of the paper is whether inflation expectations are 'anchored': roughly, do people clearly believe that inflation will stay reliably low? They look at five possible ways of assessing it: for example, do expectations vary very widely across the population rather than most people being in the same sort of place? Do expectations jump all over the place from one time period to the next? And so on.

On all five criteria, they find that the business managers they polled did not have settled inflationary expectations. As the abstract puts it

Managers of these firms display little anchoring of inflation expectations, despite twenty-five years of inflation targeting by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, a fact which we document along a number of dimensions. Managers are unaware of the identities of central bankers as well as central banks’ objectives, and are generally poorly informed about recent inflation dynamics. Their forecasts of future inflation reflect high levels of uncertainty and are extremely dispersed as well as volatile at both short and long-run horizons. Similar results can be found in the U.S. using currently available surveys.This leads into all sorts of serious cogitation about the efficacy of monetary policy, the need for central banks to communicate better, and how people form their inflation expectations, and if you're a monetary policy tragic you'll love it.

But it also says something pretty damning about the level of ignorance among New Zealand's business community. I'll pass quickly over the facts that only 31% of managers could identify the main objective of the Reserve Bank, and that only 30% could name its governor (even when, in both cases, they were given prompt sheets of the possible answers), and concentrate on this one. Here's a table (clipped from table 7 of the paper) of responses to the question, what inflation rate do you think the RBNZ is trying to achieve? Column 1 shows the possible answers, column 2 shows the percentage of managers who opted for each possible answer, and column 3 shows what they thought actual inflation would be over the following year.

As the authors summarised it, "Of the respondents, only 12% correctly responded 2%, although an additional 25% said either 1% or 3%, the bottom and top of the target range of the RBNZ. But 15% said the RBNZ’s target inflation rate was 5%, 36% said the target was more than 5%, with 5% of respondents saying that the RBNZ’s target inflation rate was 10% or more". Just over half (50.9%) thought that inflation was going to be at least 5%. It turned out to be 0.8% (year to December '14).

Now, I know that there will be a lot of managers doing a perfectly acceptable job of getting the widgets made and out the door, with or without knowing what the rate of inflation is or exactly what the Reserve Bank is trying to do. I'd suggest, particularly if they come anywhere near the strategic planning end of the business, that they're nowhere near as effective as they might be, but there's surely a valid role for heads down, bums up, and get the salads packed and despatched.

And I know that those of us who are into macroeconomics can sometimes forget that others aren't as familiar with the jargon and the details, and that you can actually have a life without delving into the national accounts or the CPI. People get caught up in their own preoccupations, but we don't all need to know the niceties of the LBW rule.

And I know that other countries can be just as bad: the paper documents a similar pattern in the US, though that's little comfort. Not many of us would like to be found on a par with what's happening in twilight Trump-or-Cruz America.

Apologetics apart, though, let's face it: this is a staggering level of ignorance. It makes you ask, among many other things, what on earth the secondary schools can have been teaching in their economics classes over the last twenty years. It leaves you thinking that one of the reasons for our well-documented issues with productivity might well be ill-equipped management. And it makes you wonder about the level of understanding voters have brought into the polling booths: as I've written before, every general election has brought proposals for changing our monetary policy regime, ranging from the potentially promising to total nonsense. How likely is it we'll get a good outcome when people have only the foggiest idea of the current arrangements?

Friday, 11 September 2015

Another blast from the past

Statistics NZ's Twitter feed just posted this fun item:

It has a link back to a piece that Stats published in 2012, 'Delving into the clothes basket - tracking women's and men's clothing in the CPI', which went back to 1924 to look at what men and women and children wore.

It's fascinating - today's girls will be pleased that they don't have to wear the woollen bloomers of 90 years ago, and today's women will be pleased they don't have to make their own clothes - and it's one of a terrific series of time capsules that Stats have unearthed and published. Last time I wrote about them, in 'The way we live now', I said that this analysis of past CPIs was "almost a complete social history in itself". It's also a great timewaster, so cancel an hour, head to my post, and follow up the links there to the various Stats publications.

For me - and here I stress this is my take, not Stats' view or interpretation - the clothes basket piece fortuitously showed the potential benefits of trade liberalisation. From the late '80s onwards, tariffs and quotas on clothing imports were lowered or abolished. The results were that clothes prices have risen much more slowly than prices more generally (as the first graph below shows) and people have been able to buy much more (as the second one shows).

And the "cost"? - "the number of jobs filled by paid employees in the clothing and knitted product manufacturing industry fell nearly 60 percent – from 9,550 to 4,120". Four million people, give or take, got a large benefit, while 5,500 people, give or take, lost their jobs. And I put "cost" in apostrophes because many - maybe all - of those people will have found other jobs, and in activities that the community values more highly than keeping a small-scale rag trade going.

It's also very likely that liberalising clothing imports was a progressive move (in the tax policy sense of "progressive" as opposed to "regressive"). At home, the household budgets of lower and middle income families, and particularly those with children, will have had one of their bigger costs reduced. And overseas, people in poorer countries will have got real jobs, instead of aid, and started down the road of economic development that will make them better off and, along the way, better customers for our exports. That's a pretty good outcome all round.

It has a link back to a piece that Stats published in 2012, 'Delving into the clothes basket - tracking women's and men's clothing in the CPI', which went back to 1924 to look at what men and women and children wore.

It's fascinating - today's girls will be pleased that they don't have to wear the woollen bloomers of 90 years ago, and today's women will be pleased they don't have to make their own clothes - and it's one of a terrific series of time capsules that Stats have unearthed and published. Last time I wrote about them, in 'The way we live now', I said that this analysis of past CPIs was "almost a complete social history in itself". It's also a great timewaster, so cancel an hour, head to my post, and follow up the links there to the various Stats publications.

For me - and here I stress this is my take, not Stats' view or interpretation - the clothes basket piece fortuitously showed the potential benefits of trade liberalisation. From the late '80s onwards, tariffs and quotas on clothing imports were lowered or abolished. The results were that clothes prices have risen much more slowly than prices more generally (as the first graph below shows) and people have been able to buy much more (as the second one shows).

And the "cost"? - "the number of jobs filled by paid employees in the clothing and knitted product manufacturing industry fell nearly 60 percent – from 9,550 to 4,120". Four million people, give or take, got a large benefit, while 5,500 people, give or take, lost their jobs. And I put "cost" in apostrophes because many - maybe all - of those people will have found other jobs, and in activities that the community values more highly than keeping a small-scale rag trade going.

It's also very likely that liberalising clothing imports was a progressive move (in the tax policy sense of "progressive" as opposed to "regressive"). At home, the household budgets of lower and middle income families, and particularly those with children, will have had one of their bigger costs reduced. And overseas, people in poorer countries will have got real jobs, instead of aid, and started down the road of economic development that will make them better off and, along the way, better customers for our exports. That's a pretty good outcome all round.

Thursday, 10 September 2015

A defining moment?

Last night we had the latest seminar from the Law and Economics Association of New Zealand (LEANZ) - AUT's Dr Lydia Cheung on "Quantitative techniques for competition analysis: An Overview, and Application to the Z Energy / Chevron Merger", which traversed market definition, modern demand estimation, and merger simulation. It was billed as "for non-economists as well as economists" - a tough challenge if you're going to take the laity through things like critical loss analysis and systems of demand equations - but she pulled it off.

It's also left me thinking about a few things, and in particular about market definition.

The trend these days for competition agencies, when considering mergers and acquisitions, is to rather downplay the importance of exact or precise definitions of markets, a trend which has been gathering some global oomph since the 2010 edition of the US merger guidelines. As an example, in the latest merger clearance for which the Commerce Commission has published its full decision (Staples/Office Depot), the Commission said (at para 49) that "it is not necessary for us to reach specific conclusions on relevant markets".

I'm somewhat uncomfortable with this, from a number of perspectives, including a legal one. While I'm not learned in the law, I have had to wrestle from time to time with the fine print of the Commerce Act, and I do wonder about the bit (s66) that allows the Commission to grant acquisition clearances. Under s66(3), the Commission must either be satisfied or not satisfied that "the acquisition will not have, or would not be likely to have, the effect of substantially lessening competition in a market" (my italics), and how can it do that, to an Act-satisfying standard, without specifying one?

Coming back to hopefully safer economics ground, I'm not sure the current move towards more fuzzy market definition is the right way to go, particularly as we may be getting closer (as Lydia explained) to being able to do a better job of taking a more robust empirical approach to measuring things like demand curves, and own- and cross-elasticities of demand. If, using things like scanner data, improved econometric methods, sophisticated consumer choice testing, and clever analysis of 'natural experiments' - what happened, say, after a fortuitous interruption to one source of supply - we can get a more scientific handle on the extent to which products are or are not substitutes for each other (and so are or are not likely to be in the same market), why wouldn't we use that information to derive empirically grounded market definition? More precise, rather than less?

It's also not clear to me - and here you can peel off if you like, as I'm venturing into some deeper undergrowth, and I may be gone for some time - it's not clear how a competition authority can sign up for applying a SSNIP test (as many agencies say they do, including the Commission in its Merger and Acquisition Guidelines, paras 3.15 to 3.21) and subscribe to a fuzzyish, not completely defined definition of a market. Sure, in many jurisdictions the SSNIP test is more paid lip service than formally implemented, but if you were to take it out over the fences, as agencies say they're committed to do, then you need the demand curve that the hypothetical monopolist faces. And how can you have a reliable demand curve for an ill-defined product?

In any event, that's one of the benefits of these LEANZ events: they get you thinking, and often across formal disciplinary lines. Get to them if you can, and maybe LEANZ ought to follow up on the feedback I got last time I wrote about them, that they ought to take the show on the road to Christchurch as well, and not just to Auckland and Wellington.

Thanks to Lydia for presenting, to AUT's Richard Meade for chairing the evening, and to AUT more generally for hosting and catering.

It's also left me thinking about a few things, and in particular about market definition.

The trend these days for competition agencies, when considering mergers and acquisitions, is to rather downplay the importance of exact or precise definitions of markets, a trend which has been gathering some global oomph since the 2010 edition of the US merger guidelines. As an example, in the latest merger clearance for which the Commerce Commission has published its full decision (Staples/Office Depot), the Commission said (at para 49) that "it is not necessary for us to reach specific conclusions on relevant markets".

I'm somewhat uncomfortable with this, from a number of perspectives, including a legal one. While I'm not learned in the law, I have had to wrestle from time to time with the fine print of the Commerce Act, and I do wonder about the bit (s66) that allows the Commission to grant acquisition clearances. Under s66(3), the Commission must either be satisfied or not satisfied that "the acquisition will not have, or would not be likely to have, the effect of substantially lessening competition in a market" (my italics), and how can it do that, to an Act-satisfying standard, without specifying one?

Coming back to hopefully safer economics ground, I'm not sure the current move towards more fuzzy market definition is the right way to go, particularly as we may be getting closer (as Lydia explained) to being able to do a better job of taking a more robust empirical approach to measuring things like demand curves, and own- and cross-elasticities of demand. If, using things like scanner data, improved econometric methods, sophisticated consumer choice testing, and clever analysis of 'natural experiments' - what happened, say, after a fortuitous interruption to one source of supply - we can get a more scientific handle on the extent to which products are or are not substitutes for each other (and so are or are not likely to be in the same market), why wouldn't we use that information to derive empirically grounded market definition? More precise, rather than less?

It's also not clear to me - and here you can peel off if you like, as I'm venturing into some deeper undergrowth, and I may be gone for some time - it's not clear how a competition authority can sign up for applying a SSNIP test (as many agencies say they do, including the Commission in its Merger and Acquisition Guidelines, paras 3.15 to 3.21) and subscribe to a fuzzyish, not completely defined definition of a market. Sure, in many jurisdictions the SSNIP test is more paid lip service than formally implemented, but if you were to take it out over the fences, as agencies say they're committed to do, then you need the demand curve that the hypothetical monopolist faces. And how can you have a reliable demand curve for an ill-defined product?

In any event, that's one of the benefits of these LEANZ events: they get you thinking, and often across formal disciplinary lines. Get to them if you can, and maybe LEANZ ought to follow up on the feedback I got last time I wrote about them, that they ought to take the show on the road to Christchurch as well, and not just to Auckland and Wellington.

Thanks to Lydia for presenting, to AUT's Richard Meade for chairing the evening, and to AUT more generally for hosting and catering.

Nothing to see here, folks, move along

No surprises in today's Monetary Policy Statement - and that's fine: it's best if central banks don't have to make abrupt moves, and it's also a good thing when market expectations, and what the RBNZ actually delivers, are lined up. One 0.25% cut today, and another one likely by the end of the year, is what everyone expected, and that's what they got. All good.

Sometimes the most interesting things are in the details of the text (pdf), but again there's not a lot to pick over this time. You may have seen some folks talking about potential recession ahead: that's not the RBNZ's view. Here's their forecast for GDP growth: the low point for growth is around now, with things picking up next year.

If I had to pick on anything, it's on the inflation outlook, and especially the outlook for the inflation that we generate here in New Zealand ('non tradables inflation'). Here's the Bank's best guess at what's going to happen.

You'll see that non-tradables inflation is expected to drop a bit more (in June it was 2.1%), and then pick up again. But inflation everywhere in the western world has turned out lower than central banks had expected: will it actually pick up again like the Bank thinks?

The reason I ask, is that domestic non-tradables inflation tends to be associated with the economy running flat tack - or in the jargon, at or above its 'potential output' level. But on the Bank's own projections (shown below), the economy isn't likely to be going flat tack (the forecast blue line in the graph never heads well above 0).

So there's still a risk that inflation, which has been somewhat stubbornly below the middle of the Bank's target 1%-3% range (and indeed, currently below the 1% end, never mind the midpoint), will stay that way. But that said, this was otherwise very much an 'as expected' announcement.

Sometimes the most interesting things are in the details of the text (pdf), but again there's not a lot to pick over this time. You may have seen some folks talking about potential recession ahead: that's not the RBNZ's view. Here's their forecast for GDP growth: the low point for growth is around now, with things picking up next year.

If I had to pick on anything, it's on the inflation outlook, and especially the outlook for the inflation that we generate here in New Zealand ('non tradables inflation'). Here's the Bank's best guess at what's going to happen.

You'll see that non-tradables inflation is expected to drop a bit more (in June it was 2.1%), and then pick up again. But inflation everywhere in the western world has turned out lower than central banks had expected: will it actually pick up again like the Bank thinks?

The reason I ask, is that domestic non-tradables inflation tends to be associated with the economy running flat tack - or in the jargon, at or above its 'potential output' level. But on the Bank's own projections (shown below), the economy isn't likely to be going flat tack (the forecast blue line in the graph never heads well above 0).

So there's still a risk that inflation, which has been somewhat stubbornly below the middle of the Bank's target 1%-3% range (and indeed, currently below the 1% end, never mind the midpoint), will stay that way. But that said, this was otherwise very much an 'as expected' announcement.

Thursday, 3 September 2015

That house price "fall"

Barfoot & Thompson have just come out with their latest sales report on the Auckland housing market. Early media commentary has tended to latch onto the fall in median price in August - as in 'First Auckland house price fall in six months' (Herald) and 'Have Auckland's house prices turned?' (NBR). Here are the B&T results, for the median price.

But hang on.

First of all, these numbers aren't seasonally adjusted, and there's always a drop in August. This year, though, the fall was minute (-0.3%) and noticeably smaller than previous years' (2011: -1.7%, 2012: -2.5%, 2013: -4.1%, 2014: -2.3%). On its face, the smaller than usual fall in a winter month is more compatible with a strengthening market than a weakening one.

And secondly there isn't much sign of a slowdown in the year on year rate of increase, which I've graphed below.

B&T say that you need to be careful with these year on year comparisons:

B&T's own conclusion is that "The most likely scenario is that prices will increase modestly in coming months from where they are at present", and I'm perfectly happy to go with their judgement call. All I'm saying here is that people may be leaping to premature conclusions that the August data don't properly support.

But hang on.

First of all, these numbers aren't seasonally adjusted, and there's always a drop in August. This year, though, the fall was minute (-0.3%) and noticeably smaller than previous years' (2011: -1.7%, 2012: -2.5%, 2013: -4.1%, 2014: -2.3%). On its face, the smaller than usual fall in a winter month is more compatible with a strengthening market than a weakening one.

And secondly there isn't much sign of a slowdown in the year on year rate of increase, which I've graphed below.

B&T say that you need to be careful with these year on year comparisons:

Fair enough, but even if the underlying increase is only 15%, or even 10%, you struggle to see a clear break with the trend of the past year and a half.August’s average price [they're using the average rather than the median here] is 15.4 percent higher than the average price at the same time last year, but making this year-on-year comparison is misleading as it infers prices are continuing to rise, when they are not. Most of the increase that has occurred year-on-year did so in the first four months of the year.In applying year-on-year price comparisons over the next quarter also requires care, as last year sales patterns were interrupted by the run in to the 2014 general election

B&T's own conclusion is that "The most likely scenario is that prices will increase modestly in coming months from where they are at present", and I'm perfectly happy to go with their judgement call. All I'm saying here is that people may be leaping to premature conclusions that the August data don't properly support.