Yesterday evening in Wellington the Law and Economics Association of New Zealand (LEANZ, here's

its spiffy new website), put on its latest seminar, 'Regulating Big Tech: Key Findings from the ACCC’s Groundbreaking Digital Platforms Inquiry', presented by Morag Bond, Joint General Manager of the ACCC's Digital Platforms Branch. There'd been an earlier one in Auckland at lunchtime.

Morag (below) did a fine job, in front of a good crowd. That was partly down to the intrinsic appeal of the topic, and partly down to coordination between LEANZ,

the New Zealand Association of Economists, and

the Competition Law and Policy Institute of New Zealand, each of whom gave the heads up to their memberships. Nice one. And hat tip to

Russell McVeagh Wellington, who generously hosted.

Morag's slides aren't up yet, so in the meantime, if you're not already familiar with it, here's

the ACCC's page on the inquiry, which includes

the press release,

an executive summary, and

the whole 619-page inquiry itself. If videos are your thing, here's

the 37 minute press conference on publication day.

Overall, my feeling remains where it was when this territory was traversed at

this year's ComCom conference: quite a lot of smoke, no clear fires. There are, to be sure, some issues that need investigation. One that should indeed bother merger regulators, for example, is the big incumbent platforms buying up fledgling businesses that might have morphed into credible competitors. It is of course (as Morag noted) open to an ACCC or ComCom to make that case now under our existing legislation, but the inquiry said it might help if the law was made more explicit. It recommended that

Section 50(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (CCA) be amended to incorporate the following additional merger factors:

(j) the likelihood that the acquisition would result in the removal from the market of a potential competitor;

(k) the nature and significance of assets, including data and technology, being acquired directly or through the body corporate

Maybe that might help to stiffen the odd judge's spine, but the reality is that a rewording doesn't ease the underlying difficulty, which remains highly vulnerable to both Type 1 error (stopping the purchase of a non-challenger) and Type 2 (allowing the purchase of a real threat). You can see how Type 1 errors might happen when every venture capitalist behind a start-up is puffing to new investors that it is The Next Big Thing. And you might well threaten the pipeline of innovation if inventors of useful complementary technology are wrongly prevented from cashing out to the guys with the big chequebooks.

In dynamic industries, as a general principle it's probably best to do as little as needed. It's fine to ping clearly anti-competitive practices ("thou shalt have no browser but My browser") if you come across them, and Morag said the ACCC has five investigations underway. But beyond that, you are dealing with a high-speed industry with strong network effects, where bigness is almost inevitable and the most likely playbook is a Schumpeterian succession of temporarily highly-profitable near-monopolies. It's true, as Morag said, that Facebook is being somewhat disingenuous when it argues that someone might topple Facebook as readily as Facebook toppled MySpace, but that's the longer-term way to bet. If you're my age, you once wrote in WordStar and worked with data in Lotus 1-2-3: where are they now?

Sit back and let it evolve is likely to be a good default competition policy strategy from another perspective. If there are real issues, for example genuine consumer concerns over privacy or data sharing - and in my view it's not yet proven that enough consumers care about the current bargain they've struck - I wouldn't underestimate the ability of markets to deal to them. Worried about the outfits tracking your every online move? Instal

Ghostery: as I write it's telling me there are no trackers following the ACCC site, four tracking ComCom's, and 13 tracking mine. Hah! Worried about the trustworthiness of a site? Instal

Web of Trust. And even the incumbents are beginning to realise that it's in their own longer-term interest not to push their luck: have a look, for example, at

'How to Set Your Google Data to Self-Destruct'.

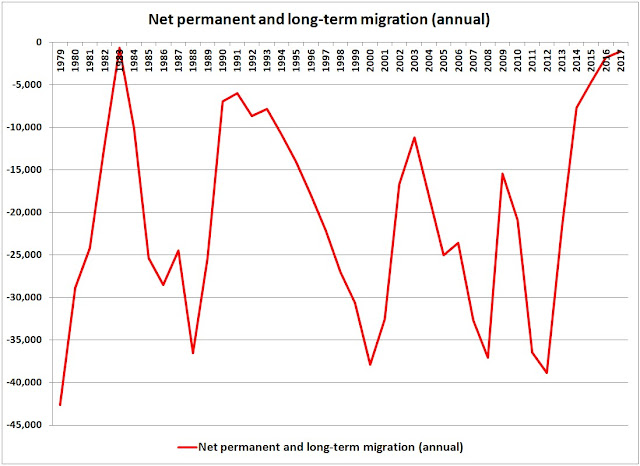

The ACCC inquiry was required in its terms of reference to consider "the impact of platform service providers on the level of choice and quality of news and journalistic content to consumers", and the upshot was that the Australian public allegedly risks losing some worthwhile public interest coverage of (for example) local politics. This is because, as shown below in a chart from the Executive Summary, online advertising has eaten the old media's classified advertising revenue, which means they can no longer afford proper "local beat" journalists and are forced to recycle cheaper celebrity gossip, clickbait, and grief porn (my words, not Morag's or the inquiry's).

But I wonder if citizen journalism and the rise of "digital natives" - media that have only ever existed online - are a better market-oriented answer than the taxpayer subsidies the ACCC recommended for coverage of local courts and local politics. As Morag mentioned, the barriers to entry for new media have dropped enormously, enabling that "long tail" of small pockets of interest to be accommodated. Even in relatively niche areas, all of us now read expert, informed, committed media, from all ends of the spectra of opinion, that didn't exist a few years back. If local politics matters to people, and it does to some, it's highly likely someone will rise to the challenge unprompted.

Maybe I'm wrong, the

North Shore Times will fall over, and the deliberations of the Hibiscus and Bays Local Board will be lost to posterity. I doubt it, but yet again, the better course is to see how it plays out before jumping to 'solutions'.