An economist colleague - oh all right, Kieran Murray of Sapere - sent me through some fascinating near-real-time economic data in Australia. It's from a partnership between illion, previously the Australian operations of Dun & Bradstreet, and Aussie economic consultants AlphaBeta.

Their very up to date data covers, among other things, consumer spending by region and by category, as well as indicators of personal or business financial distress. Here for example is the overall consumer spending graph. The distinction between the 'crisis' and 'stimulus' periods mainly reflects the impact of the A$750 cheques that went out from the end of March to over six million lower-income Australian households.

The sectoral breakdown of spend shows exactly how we've managed through lockdown: the biggest increases were on food delivery, online gambling, furniture and office (it's become evident from Zoom meetings that many folks, to start with, didn't have anything like a half-way equipped home office), home improvement (ditto), and alcohol and tobacco. While the bets and the booze don't reflect very well on how we've spent our enforced time at home, there's a small solace that the next largest increase was on pet care. Subscription TV was up too, though not as much as I'd have expected (11% more than in a 'normal' week).

This is excellent stuff. Yet again we've shown, if we put our minds to it, that we can actually get a much better handle on the real-time state of the economy than we've had before: if the Australian Treasury or others with skin in the game didn't know the likely scale and shape of the covid hit to retail sales, they do now.

Next thing is to keep this going on the other side of covid. As I've been banging on for a while (eg here and here), over the years we've had inadequate indicators of the cyclical state of the New Zealand economy: they've been too few and they've been too late. As we're now discovering in both New Zealand and Australia, there are treasure troves of near real-time data all over the place that can be used to fill in the gaps. Hopefully operators like illion and AlphaBeta will keep these data flows going but if not, and in any event, Stats NZ and their counterparts ought to be getting alongside these data providers and developing a suite of timely high-frequency indicators. Covid's been no time to be blundering in a statistical fog, but neither is anytime else.

Wednesday, 29 April 2020

Friday, 24 April 2020

Getting even more real

No sooner had I posted about some promising 'dashboards' from Sense Partners and the Treasury, which aim to use a variety of data to try and gauge exactly where economic activity has got to through lockdown, than Stats also came to the party with its own data portal (media release here, portal itself here).

It's excellent. They've even found a data sources I'd never heard of, and I've played around with quite a few. It's from the GDELT Project, showing weekly economic sentiment (it's in the 'Economic'/'Confidence' section). I'm not sure whether it's New Zealand specific or global, but either way it's informative.

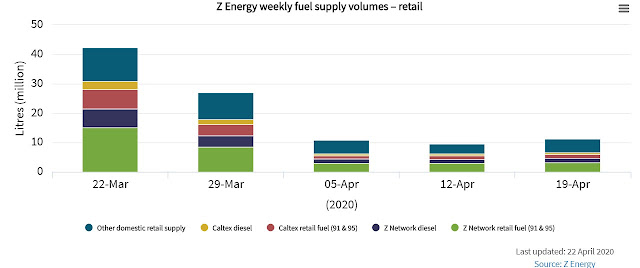

Here's Z's weekly fuel sales (in 'Economic'/'Activity'): hat-tip to them for sharing.

Gift horses and mouths and so on, but if the portal could organise some weekly (or even daily) electronic card expenditure data, that would be a useful extension to what is already a good (and easy to use) data set.

Stats says all the right things about the data being other peoples', not theirs, and go look up the methodology of the original creators if you want to find out more about what they mean and how they've been created.

All good stuff - and let's hope that on the other side of covid, Stats give some thought (and Treasury gives some money) to a permanent improvement in our ability to keep our finger on the day to day pulse of the economy.

It's excellent. They've even found a data sources I'd never heard of, and I've played around with quite a few. It's from the GDELT Project, showing weekly economic sentiment (it's in the 'Economic'/'Confidence' section). I'm not sure whether it's New Zealand specific or global, but either way it's informative.

Here's Z's weekly fuel sales (in 'Economic'/'Activity'): hat-tip to them for sharing.

Gift horses and mouths and so on, but if the portal could organise some weekly (or even daily) electronic card expenditure data, that would be a useful extension to what is already a good (and easy to use) data set.

Stats says all the right things about the data being other peoples', not theirs, and go look up the methodology of the original creators if you want to find out more about what they mean and how they've been created.

All good stuff - and let's hope that on the other side of covid, Stats give some thought (and Treasury gives some money) to a permanent improvement in our ability to keep our finger on the day to day pulse of the economy.

Saturday, 18 April 2020

Getting real

We don't have an adequate grasp on the real-time state of the economy. We need much more close-to-real-time data.

That's it. The rest of this post is a riff on the same theme.

As covid wreaks its damage, it would be good to know, now, what that damage is: what's the initial hit to GDP? Where are the worst impacts? How are the knock-on ripple effects going? Among many other things, it would inform how hard fiscal policy needs to fight back. As it is, we - and many other countries - are at the "Oops, did I say $10 billion? I meant $40 billion" stage of Finance Ministers' groping for what the fiscal response needs to be.

Crises apart, we should always have had better high frequency cyclical data than we've actually had. As Michael Reddell said recently in the 'Measuring the slump' post on his Croaking Cassandra blog, "We and Australia are the only two OECD countries without a monthly CPI, our GDP estimates (quarterly only, as with most countries) come out only with a very long lag, we don’t have a monthly industrial production series, and we still don’t have an income-based measure of GDP". These deficiencies have been known for a long time - I can remember discussions over the years at Stats' Advisory Committee on Economic Statistics (since disbanded) - but the debate never got as far as prising open Treasury's chequebook.

Michael had several constructive ideas on how to improve things, including having Stats publish the monthly results from its rolling quarterly Household Labour Force survey, and having Stats also "look at hosting some sort of dashboard pulling together, and making openly available, all manner of formal and informal economic indicators. There have to be lots".

The good news is that at least two parties (though not Stats, yet) have had a go at dashboards.

First out of the blocks was Sense Partners: you can access their latest six-variable dashboard here. It's good, isn't it? I especially liked the electricity generation graph (below). You'd think that it must be reasonably close to the fall in GDP, and is suggesting something like a drop of close to 20% in output since late March (though there may be seasonal stuff going on, too).

They were closely followed by Treasury, who've just put out theirs (media release here, access to the pdf dashboard here). Personally I felt the Sense set gave me more of a real-time feel, though Treasury's information was interesting in its own right, especially the traffic data and the data on uptake of the job subsidy scheme (below).

The next thing that would be really useful would be some composite indicator of all these glimpses of the overall underlying reality. As it happens economists have a nifty way of devising one: it's called 'principal components', and works by assembling a lot of data, hopefully all related (positively or negatively) to some underlying common influence, and then analysing it econometrically to see if you can identify a common background factor.

Treasury's dashboard helpfully included some international data, and one of the series shown was, indeed, one of those composite indicators, for the US. It looks like this.

If you want to follow the series yourself it's here at the Fed of New York site, and there is a (short) write-up of how it all works here. The devisers of the index have calibrated it so that percentage changes in the index can be (give or take) read as percentage changes in GDP, or as they put it, "a reading of 2 percent in a given week means that if the week’s conditions persisted for an entire quarter, we would expect, on average, 2 percent [GDP] growth relative to a year previous". So we know that if early-April conditions persisted for the whole of the June quarter, US GDP would be some 9% lower.

Can we be sure that the weekly economic index does in fact track US GDP pretty well? Yes, we can, as you can see below (this is from Chapter 1, 'US economic activity during the early weeks of the SARS-Cov-2 outbreak', in Issue 6 of the Centre for Economic Policy Research's covid economics series, well worth following).

Two things to finish with.

One, obvs, wouldn't it be nice if someone did the same number crunching on New Zealand data and gave us close to a real-time reading on where GDP has got to? And yes, I'm happy to be part of the effort if anyone feels the urge to get it done.

Two, the wider point about the limited range of our current official cyclical data, and the speed with which what we have gets published, needs to be addressed. You can't go to a competition or regulation conference these days without people blathering on about how 'big data' enables market power, or threatens privacy, but you don't see anything like the same focus on how the torrents of big data could be used to generate near-real-time cyclical gauges.

It's fine to have the business as usual, industrial strength, quality-assured things like the quarterly national accounts. But as Grant Robertson and the lads at Treasury - and the rest of us - are finding out, there's a big role for the cheap and cheerful but timely and informative indicators, too. We've shelled out some $9 billion on wage support: in the greater scheme of things a couple of mill to zero in on where we actually are would be money very, very well spent.

That's it. The rest of this post is a riff on the same theme.

As covid wreaks its damage, it would be good to know, now, what that damage is: what's the initial hit to GDP? Where are the worst impacts? How are the knock-on ripple effects going? Among many other things, it would inform how hard fiscal policy needs to fight back. As it is, we - and many other countries - are at the "Oops, did I say $10 billion? I meant $40 billion" stage of Finance Ministers' groping for what the fiscal response needs to be.

Crises apart, we should always have had better high frequency cyclical data than we've actually had. As Michael Reddell said recently in the 'Measuring the slump' post on his Croaking Cassandra blog, "We and Australia are the only two OECD countries without a monthly CPI, our GDP estimates (quarterly only, as with most countries) come out only with a very long lag, we don’t have a monthly industrial production series, and we still don’t have an income-based measure of GDP". These deficiencies have been known for a long time - I can remember discussions over the years at Stats' Advisory Committee on Economic Statistics (since disbanded) - but the debate never got as far as prising open Treasury's chequebook.

Michael had several constructive ideas on how to improve things, including having Stats publish the monthly results from its rolling quarterly Household Labour Force survey, and having Stats also "look at hosting some sort of dashboard pulling together, and making openly available, all manner of formal and informal economic indicators. There have to be lots".

The good news is that at least two parties (though not Stats, yet) have had a go at dashboards.

First out of the blocks was Sense Partners: you can access their latest six-variable dashboard here. It's good, isn't it? I especially liked the electricity generation graph (below). You'd think that it must be reasonably close to the fall in GDP, and is suggesting something like a drop of close to 20% in output since late March (though there may be seasonal stuff going on, too).

They were closely followed by Treasury, who've just put out theirs (media release here, access to the pdf dashboard here). Personally I felt the Sense set gave me more of a real-time feel, though Treasury's information was interesting in its own right, especially the traffic data and the data on uptake of the job subsidy scheme (below).

The next thing that would be really useful would be some composite indicator of all these glimpses of the overall underlying reality. As it happens economists have a nifty way of devising one: it's called 'principal components', and works by assembling a lot of data, hopefully all related (positively or negatively) to some underlying common influence, and then analysing it econometrically to see if you can identify a common background factor.

Treasury's dashboard helpfully included some international data, and one of the series shown was, indeed, one of those composite indicators, for the US. It looks like this.

If you want to follow the series yourself it's here at the Fed of New York site, and there is a (short) write-up of how it all works here. The devisers of the index have calibrated it so that percentage changes in the index can be (give or take) read as percentage changes in GDP, or as they put it, "a reading of 2 percent in a given week means that if the week’s conditions persisted for an entire quarter, we would expect, on average, 2 percent [GDP] growth relative to a year previous". So we know that if early-April conditions persisted for the whole of the June quarter, US GDP would be some 9% lower.

Can we be sure that the weekly economic index does in fact track US GDP pretty well? Yes, we can, as you can see below (this is from Chapter 1, 'US economic activity during the early weeks of the SARS-Cov-2 outbreak', in Issue 6 of the Centre for Economic Policy Research's covid economics series, well worth following).

Two things to finish with.

One, obvs, wouldn't it be nice if someone did the same number crunching on New Zealand data and gave us close to a real-time reading on where GDP has got to? And yes, I'm happy to be part of the effort if anyone feels the urge to get it done.

Two, the wider point about the limited range of our current official cyclical data, and the speed with which what we have gets published, needs to be addressed. You can't go to a competition or regulation conference these days without people blathering on about how 'big data' enables market power, or threatens privacy, but you don't see anything like the same focus on how the torrents of big data could be used to generate near-real-time cyclical gauges.

It's fine to have the business as usual, industrial strength, quality-assured things like the quarterly national accounts. But as Grant Robertson and the lads at Treasury - and the rest of us - are finding out, there's a big role for the cheap and cheerful but timely and informative indicators, too. We've shelled out some $9 billion on wage support: in the greater scheme of things a couple of mill to zero in on where we actually are would be money very, very well spent.

Thursday, 9 April 2020

Go your own way, or else

Last week the Supreme Court published its Lodge judgement (media release here). By way of background the Commerce Commission had taken a range of Hamilton real estate agents to court for an alleged price-fix breach of s30 of the Commerce Act, alleging that they had collusively agreed to charge their customers TradeMe listing fees rather than absorbing them. The agencies were responding to a proposed thumping great rise in TradeMe's charges for online real estate listings. Before the increase, agencies would often absorb the charge, post increase they reckoned they wouldn't be able to afford to.

Many of the agencies settled and paid (even by my cartel-hostile standards) swingeing penalties. Lodge (the company and its principals) fought on. They won in the High Court ('...and then the wheels came off'). The Commerce Commission took it to the Court of Appeal and prevailed ('The wheels are back on'). Lodge took it to the Supreme Court, and as we now know, have lost.

In the process we've ended up in a better place. We've now got greater clarity on exactly what's involved in that 'meeting of minds' that turns what might have been simultaneous and identical but unilateral reactions into illegal collusion. We've also got a better steer on whether collective agreement on part of a product or service offering - even if only a smallish part of the overall price - constitutes 'controlling' the price (it generally does).

On the first point, the key bit at [54] (footnote omitted and Giltrap reference added) is

That was exactly the case in the Hamilton house market. At [157]

It is easy to think of other circumstances: where an industry is whacked with some new industry-wide levy, for example, the temptation may be there to have a natter in the industry forum and agree to pass it on. Resist the temptation: you'll be breaching s30. As I put it after the original High Court case, "How much of a cost to absorb, and how much to pass on, needs to be your own independent decision".

There's only one bit of the judgement I'd quibble with, and in the greater scheme of things it doesn't matter, but I wonder about the reasoning in [159] where the Court felt that the Lodge parties seemed to want to have it every which way:

Many of the agencies settled and paid (even by my cartel-hostile standards) swingeing penalties. Lodge (the company and its principals) fought on. They won in the High Court ('...and then the wheels came off'). The Commerce Commission took it to the Court of Appeal and prevailed ('The wheels are back on'). Lodge took it to the Supreme Court, and as we now know, have lost.

In the process we've ended up in a better place. We've now got greater clarity on exactly what's involved in that 'meeting of minds' that turns what might have been simultaneous and identical but unilateral reactions into illegal collusion. We've also got a better steer on whether collective agreement on part of a product or service offering - even if only a smallish part of the overall price - constitutes 'controlling' the price (it generally does).

On the first point, the key bit at [54] (footnote omitted and Giltrap reference added) is

Tipping J [in the classic Giltrap cartel case] was making it clear that there will be no arrangement unless the expectation that arises from the consensus is such that it can be inferred that the parties to the consensus have assumed a moral obligation to each other. We would substitute “made a commitment” in place of “assumed a moral obligation”. Calling such an obligation a “moral obligation” introduces morality into a context where it adds nothing. It seems to us that the essential thing is that a commitment is made: one that is not legally binding but is sufficient to be the basis of an expectation on the part of the other parties that those who made the commitment will act or refrain from acting in the manner the consensus envisages.Or as the Court wrapped it up at [58]

We summarise the test in this way. If there is a consensus or meeting of minds among competitors involving a commitment from one or more of them to act (or refrain from acting) in a certain way, that will constitute an arrangement (or understanding). The commitment does not need to be legally binding but must be such that it gives rise to an expectation on the part of the other parties that those who made the commitment will act or refrain from acting in the manner the consensus envisages.On the second issue of 'controlling' price, you might argue that collectively agreeing on an approach to the TradeMe fee made no real difference, given that the TradeMe fee was only a small part of the overall cost of the service, which was of course dominated by the percentage-of-your-house-value estate agent's fee. But the Supreme Court harked back to the Caltex case where the petrol companies had collectively agreed to to remove a previously free carwash: at [143]

In that case, three petrol retailers entered into an arrangement to abandon a practice of offering a free carwash to any person making a purchase of $20 or more of petrol. A carwash was worth about $2 at the time. The arrangement did not involve any agreement as to the prices that would be charged for petrol or carwashes. Salmon J found that the arrangement had the effect of controlling the price of petrol sold by the parties to the arrangement because it restrained the free action of the parties in setting the priceand the Court said at [145]:

These [Caltex] authorities as to what amounts to “controlling” prices are longstanding and we see no reason to depart from them.It is possible that some components of an overall deal might indeed be so small as to be competitively insignificant: at [155]

We accept that there will be cases where the component of the overall price that is affected by the arrangement is so insignificant that it cannot have the effect of controlling the overall price, assuming that the overall price is otherwise determined by market forces.The way to think about it, the Court said at [156] is:

the correct position is that price includes a component of the price unless that component is insignificant in competition terms. We do not see this as a mathematical calculation, howeverand that must surely be right. You may well be up for a $20K overall house-selling cost either way, but you might well go with the agency that swallows the relatively insignificant TradeMe fee rather than the one that doesn't.

That was exactly the case in the Hamilton house market. At [157]

The evidence established that Trade Me listings were a significant factor in competition between the Hamilton agencies, as both the High Court and Court of Appeal foundand at [160]

The effect of the arrangement in relation to the Trade Me listing fee controlled the overall price of the services provided by the agencies by interfering with the competitive process that would otherwise have applied.So we've got to a clear statement of how the law applies to quite a common situation businesses may encounter. The Court said that there were similarities, for example, with the air cargo cases, where airlines were faced with various new security surcharges (post 9/11) and collectively (but in the end illegally) agreed to pass them on in full to their air cargo customers rather than making independent competitive decisions on whether to absorb them in full or in part.

It is easy to think of other circumstances: where an industry is whacked with some new industry-wide levy, for example, the temptation may be there to have a natter in the industry forum and agree to pass it on. Resist the temptation: you'll be breaching s30. As I put it after the original High Court case, "How much of a cost to absorb, and how much to pass on, needs to be your own independent decision".

There's only one bit of the judgement I'd quibble with, and in the greater scheme of things it doesn't matter, but I wonder about the reasoning in [159] where the Court felt that the Lodge parties seemed to want to have it every which way:

They say on the one hand that the new Trade Me listing fee was so high that it was a natural reaction for agencies to refuse to absorb it, given the considerable cost to them if they did so, but on the other that the fee was such a small component of the overall price of their services that it should be treated as insufficiently significant in competition terms to bring the agreement to fix or control it within the prohibition in s 30.I don't see an intrinsic contradiction at all. In a very low-margin industry, for example, it is entirely possible to conceive of a cost that is very significant to the suppliers' profitability but is still only an insignificantly small part of the end-customer price. But that's neither here nor there: the big picture is the law is now clearer, and the necessity to do your own thing now even more obvious.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)