There’s a big bunch of Budget documents handed out to the serried ranks of analysts packed into the pre-Budget ‘lock-up’ in Parliament’s Banqueting Hall, and the place I always like to start unpacking them is the economic forecasts: are they reasonable, or (in particular) are they flattering the prospects for the fiscal accounts? I’ve shown the main forecasts below, and they look more or less reasonable. I reckon the immediate economic outlook could be a bit weaker than allowed for – consumer spending, in particular, could turn out weaker (while there was a lot else also going on, Smith & McCaughey closing was just another indicator of households pulling back from spending), and we’ll have to wait and see whether the expected improvements in corporate profitability and national productivity growth materialise as anticipated. I have my reservations about the predicted track for the fiscal deficit (the ‘OBEGAL’ in the chart), as discussed later in this post, but as far as the economic forecasts go, the overall picture of difficult conditions now, ho-hum conditions in 2024-25, and rather better times beyond that, looks a commonsensical enough take.

A lot of attention will no doubt be given to the headline OBEGAL balance and in particular to the fact that it will not be back in surplus until the 2027-28 June year, a year later than previously anticipated. I don’t think this is a big issue, even if it continues an unhelpful recent tradition of pushing the “we’ll be in surplus” year out by a year, every year. I’m not sure an over-aggressive return to surplus would have made much sense in a weakish economic environment, and even at this slower-pace return to surplus we would end up with net government debt still at relatively low levels by the standard of other developed economies.

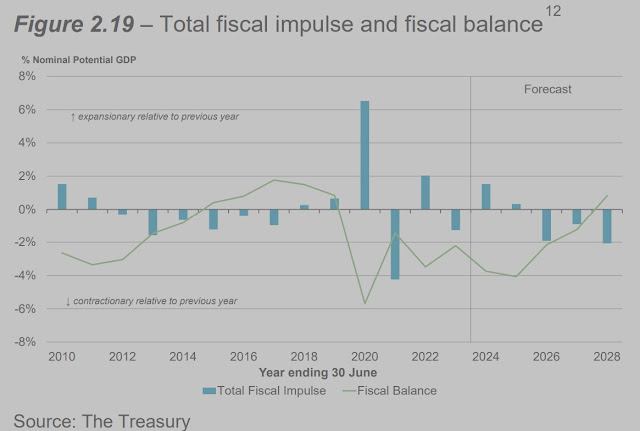

And in any event the fiscal balance, while it’s relevant to

eventually stabilising government debt and later starting to pay it back, isn’t

the best guide to one of the more important aspects of the Budget, namely

whether it boosts or brakes the economy, and whether that boosting or braking

helps or hinders the Reserve Bank’s job, which is also simultaneously trying to

steer the near-term course of the economy. That’s better captured by the ‘fiscal

impulse’ (shown below), and the good news is that the Treasury and the Reserve

Bank are no longer so obviously at loggerheads. The previous government’s 1.7%

boost to GDP from fiscal policy in 2023-24, which clearly complicated the Bank’s

job, has been followed by a more or less neutral stance in the current June

2024-25 year, and by fiscal tightening in the years beyond that. The Reserve Bank’s

job is now a bit easier. There is a wrinkle – the Reserve Bank may well have

been expecting an outright tightening of fiscal policy over the coming year as

opposed to the broad neutrality that’s now on the books – but I’ll settle for

the two of them no longer being at odds.

The improved coordination of fiscal and monetary policy is a distinct plus in this Budget, as is the reversal of the stealth tax ‘bracket creep’ of recent years when income tax thresholds were not raised in line with inflation. As Nicola Willis pointed out in her Budget speech, “The median full-time wage and salary earner now earns $73,000 a year and is in the one of the highest tax brackets. A minimum wage worker can face a marginal tax rate of 30 per cent”. That needed fixing, and has been to a degree, though I would (perhaps unrealistically given the limited room for fiscal giveaways) have liked to see a commitment to keep on adjusting the thresholds in the future.

But there are also issues that bother me.

One is that there has clearly not been enough money allocated to

keep government services going at their current levels or pay for new programmes.

The Budget Economic and Fiscal Update (the ‘BEFU’) says (p37) that “the

Government has $0.9 billion average per annum available to fund all new

initiatives and other cost pressures at Budget 2025 … It is difficult to estimate how much of the

Budget 2025 operating allowance will be needed to meet future cost pressures.

However, in recent times a large portion of the funding allocated at Budgets

has been used to meet cost pressures faced by existing services”. In other

words, just paying the higher wage bills will likely eat up all (or more than

all) of what’s budgeted.

And beyond 2025 it’s also likely there won’t be enough money

to keep everything running unless something else gives. To be fair, the Budget

fesses up: “The high-level analysis indicates that the future budget allowances

are unlikely to be sufficient to cover future cost pressures on existing

services. This means any shortfall and spending on new initiatives will need to

be offset by expenditure savings, reprioritisation or revenue raising policy

changes for each of the next three Budgets for the Government to manage within

the signalled budget allowances. This will involve difficult choices and

trade-offs for the Government which are likely to become harder over time”. The

Fiscal Strategy Report says (p4) that “Managing within $2.4 billion [operating]

allowances will therefore be challenging”: “challenging”, I’d suggest, is a

euphemism for “impossible” (especially if you look at the long list of ‘Specific

Fiscal Risks’, ‘Committed or Announced Intent that may have Fiscal Implications’

and ‘Time-limited Funding’ from p65 in the BEFU, and which will very likely put even further

pressure on the public purse). Maybe there will indeed be enough savings or

extra revenue found somewhere to make everything add up, but I for one wouldn’t

be surprised to see the OBEGAL turn out worse than currently forecast, continuing

the pattern of kicking the fiscal issues can down the road a bit further.

Another is the infrastructure spend. Yes, the Budget speech said

that “In 2024, the Government is overseeing a record level of capital

investment to deliver the infrastructure on which New Zealand’s growth depends.

More than $68 billion is forecast to be spent on infrastructure by the Crown,

Crown entities and KiwiRail over the next five years”. That’s great, and to be

fair (just looking at transport) in recent years we’ve seen things like the

Waikato Expressway, the extension of the Northern Motorway to Warkworth, and

easier access to the airport via the Waterview tunnel which have eased previous

bottleneck nightmares. But while $13.6 billion a year in new stuff is all good,

you have to remember that depreciation (the cost of keeping the existing stuff

going) is a sizeable $8.0-8.5 billion a year (see Note 10 to the government’s Forecast

Financial Statements): the net addition of infrastructure is a rather less

impressive $5.0-5.5 billion a year. I very much doubt if that’s enough given

the existing infrastructure deficit and likely new commitments (eg funding the

electrification of cars).

And finally, one of the biggest issues for successive government of all stripes has been the quality of outcomes from every public dollar spent: you only have to look at falling educational standards, or the unavailability of medical specialist advice within reasonable timeframes. The Budget is singing the right song – in the Budget speech, “the Government has a clear expectation that public agencies must strengthen their focus on delivering results. We have set clear targets to improve results in health, education, law and order, employment, housing and the environment, and we are focused on delivering them” – but I struggled to see the initiatives or new ways of working that would make the aspiration more credible.